The Lens of Strength and Compassion

I did not set out to become an artist.

I was a young college student asking questions, the difficult kind that cannot be answered in a classroom. Students like me received exposure while studying, but traditional methods of addressing new concepts and issues are not always enough. Discussions concerning international trauma in places like Croatia, Cambodia, and Rwanda simply do not do justice for the people there. Traveling as an aid relief worker gave me opportunities to explore my questions and cultivated grounds for developing personal beliefs. My artistry evolved as I documented my experiences.

I moved from a place of theorizing with scholars on the reasons for an ethnic cleansing in Bosnia to knowing firsthand the incredibly strong communities developing in refugee camps. Having read media articles and briefs, empirically explaining the Bosnian genocide, I was not expecting to play with children in the refugee camps. These were the very same children who had survived genocide, refugee exodus, and arrival to camp.

As I took photographs of the older children organizing games for the younger ones, their care for each other struck me as incredible. I was continually amazed when I discovered that a few individuals in the community were dedicated to educating all of the children in refugee camps. They were without supplies, without official teachers, but committed to each other’s success.

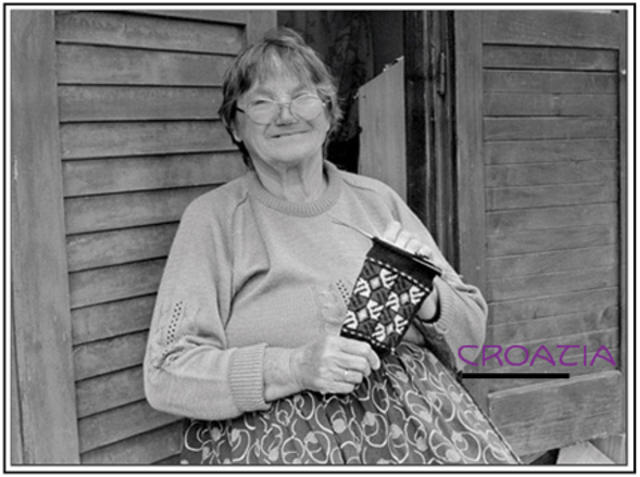

Serving alongside strong individuals who continued to provide for their community caused a shift in me. When I began shooting film, I was merely documenting with no connection through the camera lens. The more I interacted with and took photos of strong individuals, the more I realized that their strength came from their service to each other. Women who knitted for the community as a part of a Red Cross project smiled at me when I took their photos. They knew how they could serve each other.

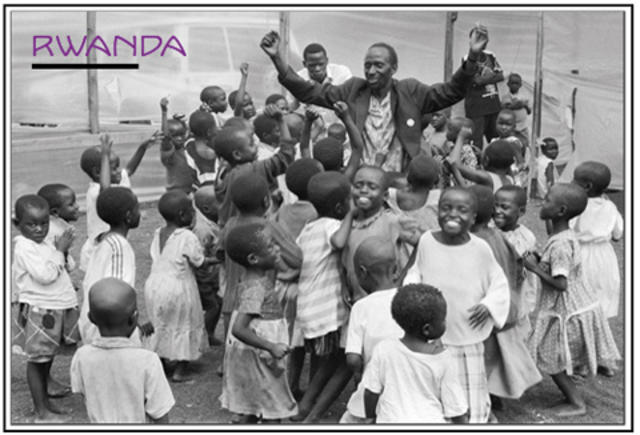

When in Rwanda, I saw the connection between service and strength again. Right after the genocide, when parents and caregivers needed to take care of their own children, the international relief community rushed in to aid unaccompanied children. Without meaning to create a difficult situation, orphanages and homes separated children from their families.Photograph by Eric GreitensInstead of providing aid for the available caregivers, aid agencies stripped them of their role of caring for their children, essentially stripping them of their strength. Those who were in roles of service, however, emanated strength. A man whose name and story I did not know provided unaccompanied children with attention, play, and games. He had no supplies, no lesson plans. This man would merely show up and the children flocked to him, smiling and clamoring for attention. His strength is evident in the moments I captured on film. His strength was not simply ‘found’ in the midst of desperate circumstances, but developed through action. The truth of strength is that we develop our strength most fully when we act to serve others.

Once I realized this, my vision changed, which also altered my photos. A motif of strong communities and individuals in service emerged. When I returned to Duke, a friend invited me to speak at a local church. She said that the members of the church wanted to learn more about the ethnic cleansing in Bosnia. I approached the meeting wishing to share experiences that had changed me. The viewers came to hear firsthand what was happening in Bosnia. I pressed the “forward” button on a slide projector and proceeded to show my photographs. A photograph of a girl drawing a house on the ground with a chalky rock appeared on the screen. The photos were mostly of individual children and families living in the two refugee camps.

With each new image, I could see that this was the first time that the members of this church had connected on a human level to what they had read about in the news. When they read about thousands of people driven from their homes, it was abstract. When they saw one family dragging a bag across a field in search of shelter, they understood. I became aware that the way I took photographs communicated clearly to a distant audience; through photography I had developed the ability to impact viewers. Their connection to peoples unknown was through my lens.

After I showed my photos to the group at the church, I offered to take questions. The group mostly had questions about daily activities, like food or laundry. Again, I realized how my travels had changed me and changed my vision. I began to discover what I value most by way of photography. Part of this comes from the artists’ relationship with their work. You can tell how someone feels about what they photo document by looking at the photos. The church group I spoke with could see my lens view. They saw my focus on the strength of service in desperate circumstances, and the noble human qualities each possessed. The pictures I shared from Croatia contrasted with most of the international aid photographs that showed desperate people and desperate babies from Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. My pictures didn’t fit that story. When looking at real human beings, it was hard to dismiss the whole war by describing it simply as “ethnic violence” or “ancient hatred.”

While some people don’t consider documentary endeavors to be “artistic,” I think if it develops purpose and aesthetic style, it is artistry. When you can see an attitude reflected in the framing of people and moments, it is artistic expression.

For me, photographing people and moments contributed to discovering my values just as much as my attitude affected my photography.

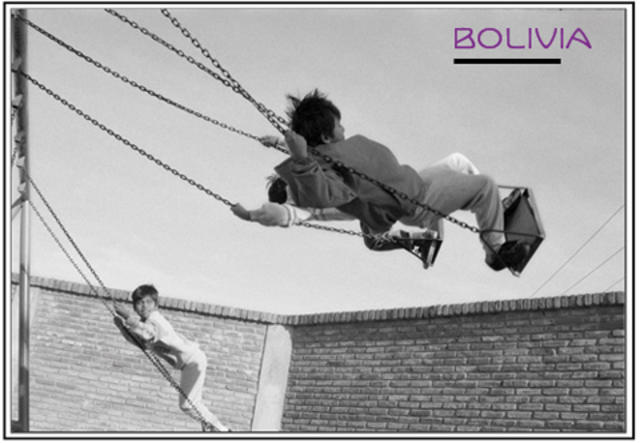

Traveling as a humanitarian and photographer confirmed my belief that everyone is capable of tremendous courage. In Bolivia I saw a few children being cared for at the children’s home Mano Amiga. They have the opportunity to see a life away from niños de la calle, or children of the street. Leaving the destructive patterns of the street, cutting, drugs, exploitation, allows the children of Mano Amiga to see a life that could be.

The volunteers in the home practiced compassion in a way that made the home special. They taught the children of Mano Amiga to take care of each other. Children lived in the home with both Jewish and Christian volunteers exhibiting charity. The Jewish volunteers lived out the word tzedakah, usually translated as charity, but the word actually has a root that is closer to “justice.” In the same home, children lived with Christian volunteers who claimed the Christian virtue of “charity.” It does not mean benevolent giving as we often think of it today, but refers to the virtue of caritas, best translated as unlimited loving-kindness.

Incredible people and situations like Mano Amiga helped me see children in desperate environments as strong. They are victims, but they have created hope and found strength. Sharing my exposure is a way of inspiring action — I hope that my photographs can change people the same way I have been changed by the experiences I photograph.

The desire to share led me to publish Strength & Compassion, a book of photos and essays. I had developed purpose with my artistry and realized the strength of photography’s ability to communicate. Connecting the two in a publication has been a method of reaching an audience. In that, Strength & Compassion embodies my beliefs and hopes for an audience. When you see photos, whether they are mine or someone else’s, I challenge you to look for what the images say. Images speak not only their own stories, but tell the viewers about the character of the artist. Art has the ability to communicate when words fail. Convictions come through connections between belief and artistry.

When I serve and photograph, I could be dissuaded from hope, dissuaded from compassion because of the injustice I witness. Instead, I am able to photograph places and moments of charity and compassion.

Eric Greitens was born and raised in Missouri and was educated in St. Louis public schools. After attending Duke University, Eric was selected as a Rhodes and Truman Scholar and attended the University of Oxford from 1996 through 2000, earning a master’s degree in development studies and a Ph.D. in politics. His doctoral thesis, Children First, investigated the ways in which international humanitarian organizations can best serve war- affected children. Eric’s book of photographs and essays, Strength & Compassion, grew from his humanitarian work. He served as a humanitarian volunteer in many of the world’s most impoverished and war-stricken countries, including Rwanda, Cambodia and the Gaza Strip. Strength & Compassion has won several awards since its 2008 release, including the Grand Prize at the 2009 New York Book Festival. In 2007, Eric used his combat pay from serving in Iraq to start The Mission Continues, where he currently serves as volunteer Chairman and CEO. The Mission Continues empowers wounded and disabled veterans to continue their service to their country and communities as citizen leaders here at home. In October of 2008, Eric was personally presented with the President’s Volunteer Service Award. Most recently, Eric was awarded a Draper Richards Fellowship, given each year to six of the nation’s leading social entrepreneurs.